Rude awakenings — the sounds of bombs dropping, aftershocks, tremors, earth-shattering moments and early-morning phone calls.

Somewhere around 4.30 a.m. on Wednesday, my childhood friend Ricky rang me up to tell me Franco Harris had passed away the night before. I was stunned beyond belief.

I cried and felt such gut-wrenching pain that I couldn’t talk. And when I did, I would return the call.

I immediately reflected on who Franco Harris was to me and how his legacy would always be cemented in my head. Memories flashed through my mind, and joy of unknown sorts warmed my heart.

Harris, half Black and half Italian, was so much more than a football player to me. He had personality and respect from day one. He was beautiful, chiseled, educated, and a beast on the football field. But there is so much more.

I grew up 40 miles north of Pittsburgh in an area considered the Cradle of Quarterbacks. Football was King. The Steelers were not.

From my earliest recollection of Steeler Football, I never relished anything close to a championship team.

The Steelers were the doormat of professional football and probably would lose their bye week if they had one back then.

Then in 1969, they hired a new head coach named Chuck Noll. Noll made a big impression by addressing his team for the first time.

He told the players that many should be looking for other types of employment. That’s how bad the Steelers were.

Noll won his first game against the Detroit Lions, then lost 13 straight to finish the season 1-13. The following season the Steelers finished a more respectable 5-9 in 1970 and 6-8 in 1971.

Year 4 for Noll and the Steelers was eagerly awaited. The buildup from one season to another was promising to a city dying for a first football championship despite having one of the oldest franchises in the NFL. Finally, they had paid their dues.

In the 1972 draft, the Steelers were slotted to pick 13th. Most thought that the Steelers would select Penn State running back Lydell Mitchell, who ran over everybody and caught everything in sight for the Nittany Lions.

Instead, the Steelers took the man who blocked for Mitchell at Penn State — Franco Harris.

“We got our man,” Noll kept saying. But, boy, did they ever. Franco Harris changed football in a city with a losing football tradition. He was a bruising runner, 6-foot-2, 220 pounds, with speed, power, endurance and the ability to catch the ball out of the backfield and make game-breaking plays. They didn’t have the YAC stat (yards after catch) back then, but he would have been among the leaders if they did.

In his rookie year as a Steeler, Harris rushed for over 1,000 yards in 14 games, only the fourth NFL rookie to do so. He found the end zone 11 times as the Steelers were becoming a very dangerous turnaround team.

The Steelers clinched the AFC Central in San Diego by beating the Chargers 24-2 at then-San Diego Stadium. The Steelers were finally champions of something.

That season was magical. It was sports theater.

Franco had his followers (Franco’s Italian Army) dressed in Italian war garb, helmets, swords, vests and the whole nine yards. The team’s placekicker, Roy Gerela, inspired Gerela’s Gorillas, with fans wearing gorilla masks. It seemed like every Steeler had a group of followers, and they were colorful and loud.

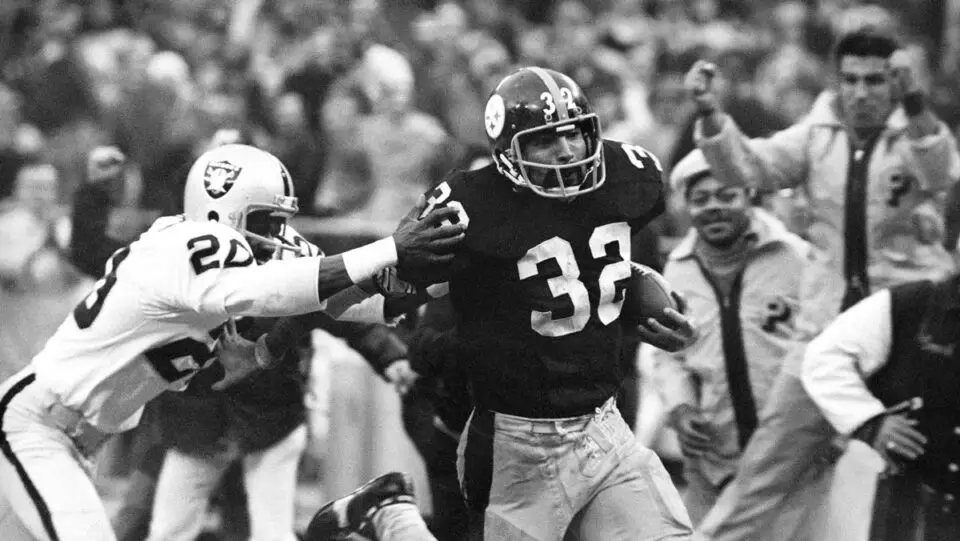

On Dec. 23, 1972, the Steelers hosted the AFC West champion Oakland Raiders at Three Rivers Stadium, only the team’s second postseason game in franchise history and first since 1947.

Win or go home … we didn’t know how to act.

The game was a defensive struggle — scoreless at halftime — and the Steelers led 6-0 on a pair of Gerela field goals late in the fourth quarter when Raiders backup quarterback Kenny Stabler ran it in from 30 yards out. With the point after, the Raiders led 7-6 with a little over a minute left.

The Steelers needed something … like a miracle … and one was about to happen. Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw, facing a fourth down with no timeouts, took the snap, evaded a defensive rush, slid to the right and launched a torpedo downfield in the direction of Steelers running back Frenchy Fuqua and Raiders defensive back Jack Tatum.

The ball ricocheted off Tatum or Fuqua, or both simultaneously. Harris, trailing the play, picked up the deflected ball before it hit the ground and ran it in for the winning touchdown.

It was indeed a miracle. The place was in chaos. Never before had an NFL game ended like this. Was it even legal? (To this day, no one knows except Frenchy). It was the most unbelievable play ever in an NFL game. Franco Harris was the hero.

That play transformed an entire city. No longer were the Steelers losers. Instead, they gave everyone hope and brought many communities together. They were becoming a nation and would soon have an iron-clad hold on their fanbase.

Even priests would shorten their sermons on NFL Sundays so as not to miss kickoff. Everybody was all in.

Franco Harris died last week at the age of 72. He won four Super Bowls with the Pittsburgh Steelers, was inducted into the Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, and became a bigger-than-life legend in Steel City.

A statue of him stands in the Pittsburgh airport depicting the play named the best in NFL history.

When Franco Harris joined the Steelers, he never knew how big his legacy would become — as a man and a football player.

But the play affectionately known as the “Immaculate Reception” was just the beginning of a career that turned a losing narrative into years of happiness and greatness.