SOLANA BEACH — As the waves crash against the rugged sandstone cliffs of Solana Beach, an unassuming concrete bunker quietly stands testament to a pivotal chapter in American history — a hidden relic built in the early 1940s waiting to unveil its secrets.

Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society historian Richard Moore, a retired nuclear physicist and Army veteran, has helped The Coast News uncover this mystery structure near a private driveway off Marview Lane, just west of Glencrest Drive.

So, what is it, and what was its purpose?

First of all, Moore says it’s not technically a bunker. The reinforced concrete dugout was one of many base-end stations and fire control structures used during World War II to identify enemy ships on the horizon and provide precise coordinates to gun batteries at Fort Rosecrans to the south.

During this time, enemy ships along the California coastline were a real threat. In late February 1942, a Japanese submarine surfaced and shelled the Ellwood oil refinery off the coast of Santa Barbara, destroying a derrick and pumphouse.

Although the attack, known as the Bombardment of Ellwood, caused minimal damage, it invoked “considerable panic” among Americans that the Japanese would continue to attack the West Coast.

In response, the Army Corps of Engineers constructed the “Santa Fe” base-end station, and the engineer’s plans and blueprints are located in the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

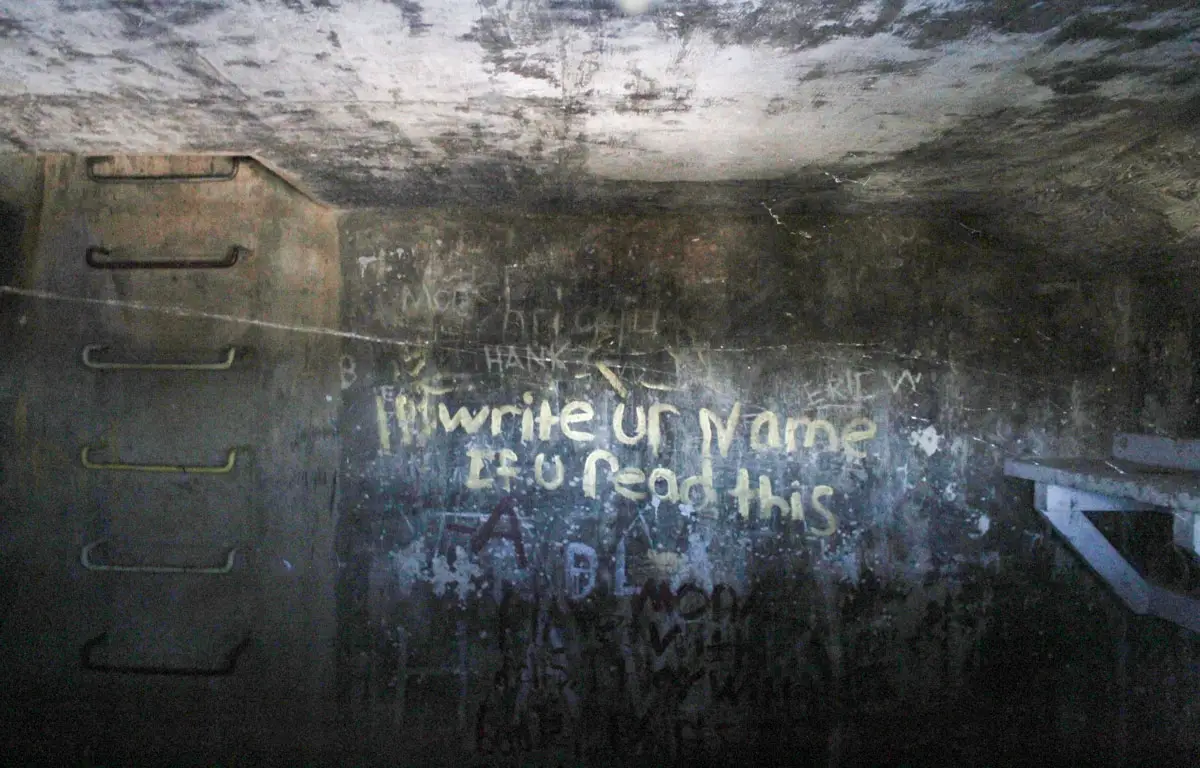

According to the documents, the Santa Fe station is 8 feet tall and 12 feet wide, with only 3 feet above the ground and visible from approximately 75 yards away. The station had no heating, lighting, running water or bathroom but was equipped with a small commercial auxiliary generator generating 125 volts. A separate concrete structure nearby contained a backup generator.

Moore said the fire control structures were solely for observing and reporting target information via telephone to a plotting room for gun batteries at Fort Rosecrans.

“The Solana Beach bunker never had artillery,” Moore said. “Most people mistakenly assume it did, but that’s not the case.”

Moore said fire control structures came in varying sizes, including a two-compartment unit, and one was even built into a fake water tower. The Santa Fe station is similar in appearance to other coastal defenses along the Point Loma Peninsula, namely Battery Ashburn at Fort Rosecrans near the entrance of Cabrillo National Monument Park.

In addition to the Santa Fe, the military’s northernmost fire control structure in Solana Beach, the Army Corps of Engineers built 12 additional units along the San Diego County coastline, stretching as far south as the U.S.-Mexico border. These defenses formed the Coast Artillery Corps, headquartered at Camp Callan on Torrey Pines Mesa, now Torrey Pines Golf Course:

Site 1: Solana Beach (fire control structure); Site 2: Soledad Mountain (fire control structure); Site 3: La Jolla Hermosa (fire control structure); Site 4: Theosophical/Sunset (fire control structure); Site 5: North Fort Rosecrans (fire control structure); Site 6: West Fort Rosecrans (gun battery Ashburn); Site 7: Cabrillo-Fort Rosecrans (fire control structure and gun battery); Site 8: Point Loma (fire control structure); Site 9: East Fort Rosecrans (searchlights); Site 10: North Island/Coronado (patrol); Site 11: Coronado Beach/Silver Strand (fire control structure); Site 12: Fort Emory (fire control structure); and Site 13: Mexican Border (fire control structure).

Before radar became available, fire control structures were strategically crucial for coastal defense. “Fire control” is defined as “technical supervision of artillery or naval gunfire on a target” or “controlling” artillery “fire” by relaying detailed target range and elevation data to nearby gun batteries.

Fire control operators used sophisticated observation tools to determine a seafaring enemy vessel’s precise distance and direction, helping ensure coastal artillery rounds hit their intended targets.

One of these tools was a depression position finder, which consisted of a sizeable telescopic lens that calculated the range or distance to a target using a triangle and trigonometry. The position finder even accounts for the Earth’s curve and how light bends. For stability, the depression position finder was mounted atop a large octagonal concrete column inside the station.

One side of the triangle is how high the instrument is above sea level (which changes with the tides and must be adjusted frequently), one angle is always 90 degrees (angle of depression), and the other is how much the instrument points downward (range to target). Once these angles are determined, the observers will know the distance to a ship up to 12,000 yards away.

The other tool was the azimuth scope, a mounted telescope used to determine an enemy ship’s position and track its movements. Further augmenting the fire control operators’ target-finding tools were six searchlights on bluffs above the beaches in Cardiff, Solana Beach, Del Mar’s Dog Beach and near Scripps Pier.

The military triangulated targets from several sources, including other fire control sites, and sightings were reported via telephone from the Santa Fe to Fort Rosecrans Battery Ashburn, one of many coastal defense batteries in California. Battery Ashburn was equipped with heavy artillery — 16-inch guns mounted on large turrets — capable of engaging enemy ships at long ranges.

During the same period, a popular local legend states that an artillery battery was located at Fletchers Cove, with a rectangular cement building serving as ammunition storage. In 1990, the North County Blade-Citizen newspaper erroneously reported this legend, further cementing the tale into local history.

However, Moore said that was just a myth. After the news article was published, retired U.S. Navy Commander Alvin H. Grobmeier wrote a letter to the publisher thoroughly debunking the newspaper’s report.

In his letter, Grobmeier also confirms that the searchlights and station at Site 1 in Solana Beach comprised the Santa Fe fire control structure.

The Santa Fe station is one of the few remaining WWII-era military structures in North County. In the decades following the war, many fire control structures were either lost to time or destroyed by homeowners. The number of structures still in existence is unknown.

Today, Santa Fe sits along a private road in a quiet Solana Beach neighborhood overlooking the ocean, a silent witness to the city’s historical events. The Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society plans to help share the structure’s story and significance with the community for future generations.

Jordan P. Ingram contributed to this report. A special thanks to Kathleen Drummond of the Solana Beach Civic and Historical Society and local historian Richard Moore for their contributions to this article.